Spirits, Lakes, and Forests: How the CSO NADA Revives Ancestral Knowledge in Gabon

Publié le 26 September 2025In Makokou, in northeastern Gabon, the forests stretch as far as the eye can see. They harbor exceptional biodiversity, but also a living memory: that of the peoples who have lived there for centuries. Before colonization, communities were settled deep within the forests, close to the rivers. The arrival of missionaries and the construction of roads disrupted this balance. Residents were relocated along the main roads, far from their ancestral lands. With this forced displacement, part of the traditional practices disappeared, weakening the intimate bond that once united humans with the forest.

For Alex Ebang Mbélé, co-founder and president of the association NADA (Nsombou Abalghe-Dzal Association), this bond is not lost. NADA works to document and secure recognition of ICCAs — Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas — places where communities preserve nature according to their own rules, inherited from ancestors and passed down orally. “The forest is the source of our energy. If we disturb it, we disturb ourselves,” says Alex.

His team travels through villages, engages with elders, and gathers stories where culture and conservation intertwine. These are tales in which spirits, lakes, and sacred trees are not static symbols, but very real guardians of biodiversity.

Magazima Lépépa: The Forest’s Regulating Spirit

In the community of Malassa, people tell the story of a young hunter who never returned from the forest. His spirit, now the guardian of the place, gave its name to this sacred forest: Magazima Lépépa.

“He still manifests himself from time to time to community members,” explains Alex. Access to the forest is strictly regulated. Those who come to hunt or gather must do so with clear and respectful intentions, preceded by incantations. A hunter who takes more than he needs is called to order: the spirit may cause him to lose his way until a relative invokes the spirit to release him.

Further on, a second sacred forest imposes another rule: one may speak only in the local Begome language. Anyone who speaks French or another language immediately experiences a sign of disapproval — sudden rain, disorientation, or a darkening of the forest. These linguistic and ritual constraints, though spiritual, have a tangible effect: they keep intact forest ecosystems rich in wildlife and flora.

Community Fishing and the Sacred Bilinga Wood and Anagoué Vine

For another community in Massaha, the communal fishing known as Itoubili takes place only once a year (during the summer holidays). At the heart of this tradition is a 14-meter-long canoe called Boualo, carved from Bilinga wood — a tree closely tied to spiritual practices — and a fish trap woven from the Anagoué vine.

Before the fishing, a young man is prepared by the elders — through isolation, restrictions, and purification. On the appointed day, the large canoe leads the way, guided by incantations and followed by other boats. When the canoe stops, that is the signal: the whole community may then fish — but only in that precise spot. The catch can fill up to 10 canoes with fish in a single day.

Gabon, 2008. Credit : Thomas Viot

For the rest of the year, the river is left to rest, allowing fish populations to regenerate. The cutting of Bilinga wood, rare and majestic, is also regulated: “We don’t fell it just anytime or anyhow. It’s bound to tradition, and that prevents disorder,” Alex emphasizes. Here, culture protects the resource.

The Cemetery Lake Turned Wildlife Sanctuary

In the heart of the Mékouma forest lies a sacred lake, once used as a cemetery. When the villages were relocated along the roads, this place was left untouched.

For the inhabitants, the animals that drink there carry the souls of the ancestors. Hunting here is unthinkable, and firing a gun is dangerous: “Something unexpected might happen to you, like getting lost in the forest,” says Alex.

As a result, the lake and the surrounding forest have become a refuge for wildlife. Elephants come to drink, birds nest, and no human activity disturbs this tranquility. NADA hopes to conduct scientific research there, but always in partnership with the community, the guardian of access.

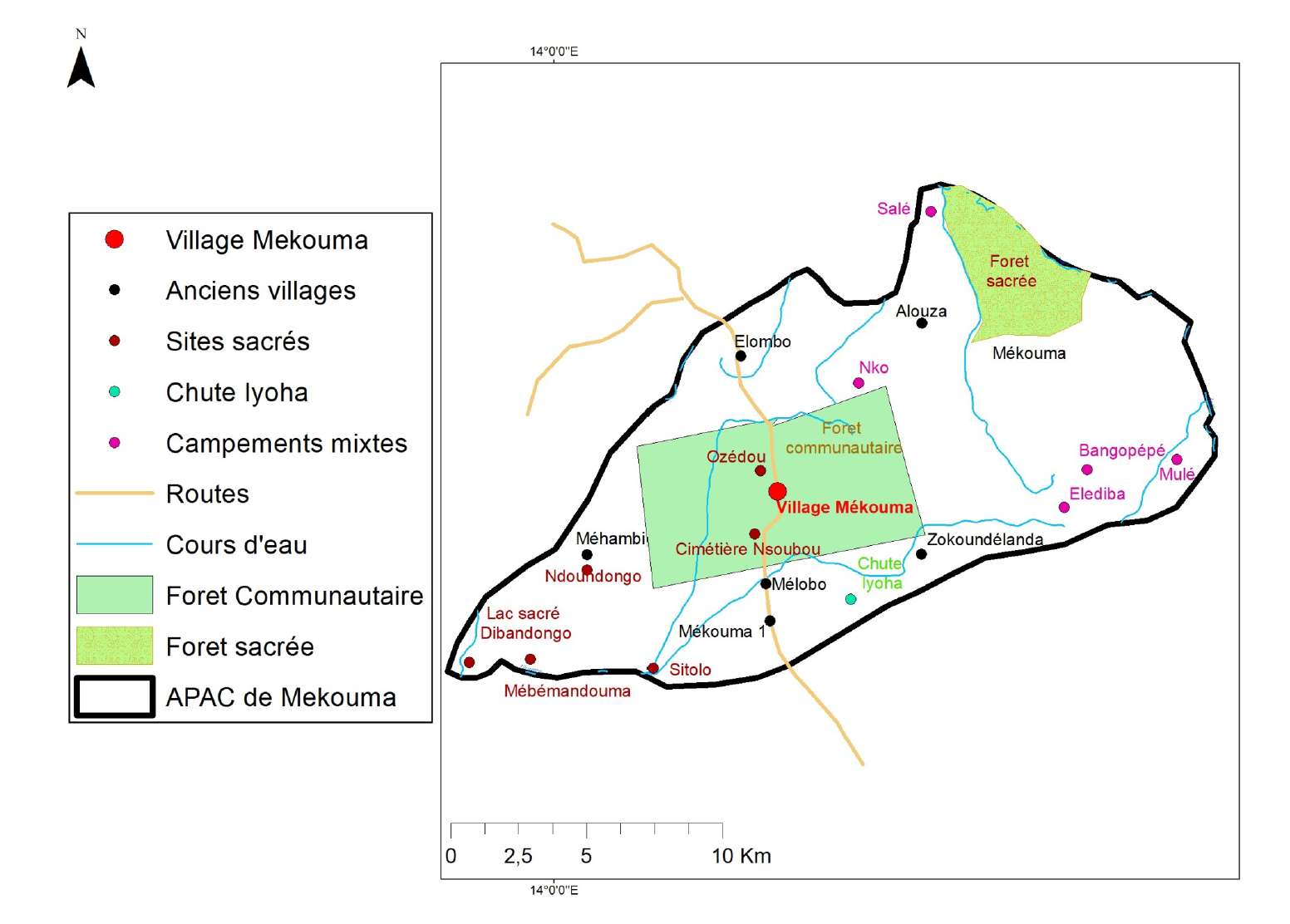

Mapping of sacred sites carried out by the CSO NADA.

The Relic Pit, Invisible Guardian

In the community of Ntolo, the arrival of evangelical missionaries disrupted traditional beliefs. Considered as witchcraft, the ancestors’ relics — skulls, ritual objects — were rejected. The elders then dug a deep pit, placing all the relics inside, thus creating a sacred well.

Even today, it remains a place of spiritual consultation: in times of trouble, people perform incantations there to seek answers. The surrounding forest is untouchable. Any attempt at agriculture mysteriously fails: “The crops yield nothing, as if the power of the relics prevented the area from being disturbed,” explains Alex. This belief discourages exploitation, thereby protecting the surrounding biodiversity.

A Vital Reconnection

These stories are not mere legends. They shape the way communities relate to their environment. They show that protecting a sacred site often means preserving an entire ecosystem.

For Alex, the distinction between protecting culture and protecting biodiversity does not exist: “The forest and people’s lives always go together. If we disturb the forest, we disturb their stability.”

By giving communities recognition of their ICCAs, NADA rekindles this bond. Elders once again take their children to the lands their grandparents spoke of. The stories come back to life, along with the awareness that nature and cultural identity are inseparable.

The Malassa community. Gabon, 2025. Credit : Marie Furtado.

Preserving these practices means keeping the forest standing, but also the soul of those who inhabit it. For reconnection with nature begins with reconnection with oneself and one’s ancestors — a path that Alex and NADA are tracing to demonstrate that these traditional practices significantly protect forests and biodiversity, before they disappear.

Click HERE to know more about NADA’s work!